Lyubov Vorontsova: Fighting the stigma surrounding people living with HIV in Kazakhstan

Date:

Thirty-five year-old Lyubov Vorontsova from Kazakhstan has been living with HIV for 15 years. While learning to live a full life and to overcome her own fears, she began to teach and help others.

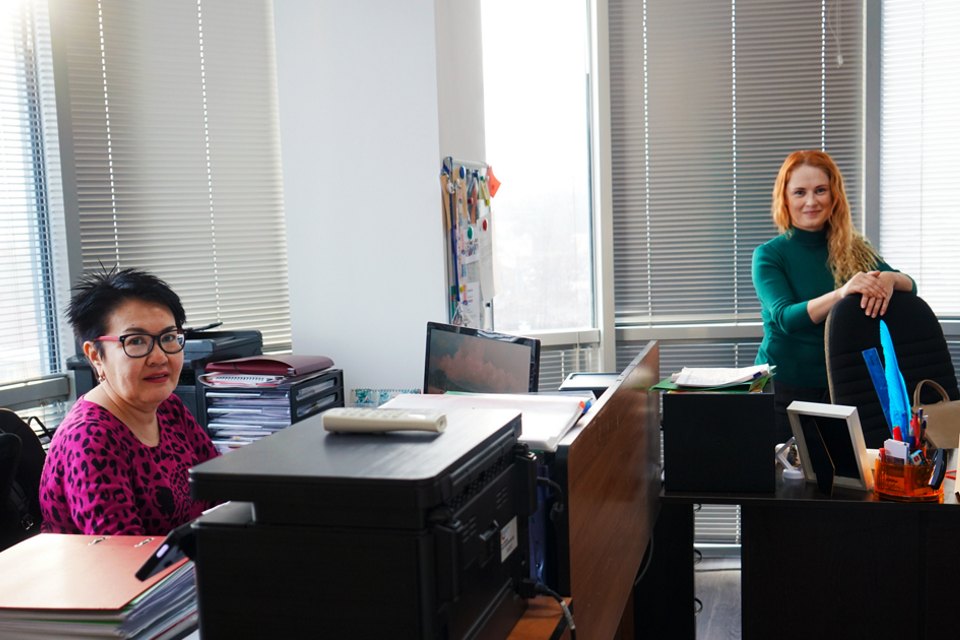

Lyubov Vorontsova is like a sun: a fire of red hair, radiant eyes, freckles, a warming smile. For several years now, Lyubov Vorontsova has been living openly with her HIV-positive status. As part of her human rights work, she gives public interviews, aiming to change people’s opinions and knowledge about people living with HIV.

According to the Kazakh Scientific Center for Dermatology and Infectious Diseases, there are more than 24,000 people living with HIV in the country and 9,000 are women. In the past, almost 25 per cent of women with HIV were offered or persuaded by doctors to have an abortion. An additional 34 per cent have never received reproductive health counseling.

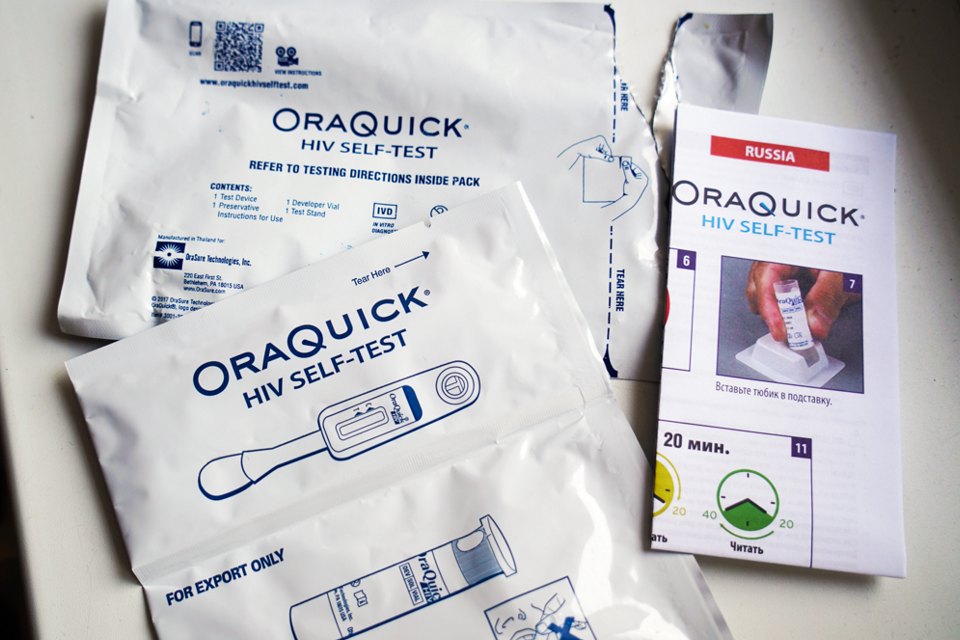

Fifteen years ago, when Lyubov was first diagnosed, this was all new to her. The Antiretroviral therapy (ART) that is a combination of HIV medicines, was only prescribed for people living with HIV who had a very low level of immunity. As Lyubov fell outside of that group, she was unable to access any therapy for the first three years after being diagnosed. During that time, she became pregnant and lived with the fear that her child may be born HIV-positive. She was able then to access treatment.

Venera and fears

When Lyubov went to the hospital to give birth, her infectious disease specialist was shocked to find out that all her medical files and laboratory tests were marked with red ink noting ‘HIV’. He raised this concern with Lyubov’s doctors, which led to the head of the antenatal clinic apologizing that her diagnosis was publicly exposed.

“I remember this careful attitude to me. I call it positive discrimination, when, on the contrary, because of my HIV-positive status, they are too protective of you in the hospital,” says Lyubov.

Lyubov’s daughter, Venera, was born calm and healthy. Family and friends supported her. Everyone helped. This meant that while she was on maternity leave, Lyubov was able to enter the Almaty Academy of Economics and Statistics to study. Lyubov says that her life is safe and she is surrounded by only good and understanding people. But she still lives with her fears.

“I'm afraid of getting sick. I’m afraid that my mother, who works in a state clinic, may hear some unpleasant things. I'm still afraid that someone might offend my daughter because of my status. It seems that I have learned to deal with this fear, but every time when people ask me, it comes up again,” says Lyubov.

I'm still afraid that someone might offend my daughter because of my status.”

From Pavlodar to Almaty

Ten years ago, Lyubov received a call from the AIDS center and was invited to a training where treatment options were discussed.

“I went and became acquainted with Alexander Pak, who had just opened an organization to help and support people living with HIV in Pavlodar. He was looking for employees and offered me a job. I agreed although I didn’t know anything about social activities,” says Lyubov.

At that time, Lyubov had just graduated from college as a certified economist, and her daughter was just over two years old. Today, Lyubov is the Project Coordinator of the Central Asian Association of People Living with HIV (PLHIV) in Almaty.

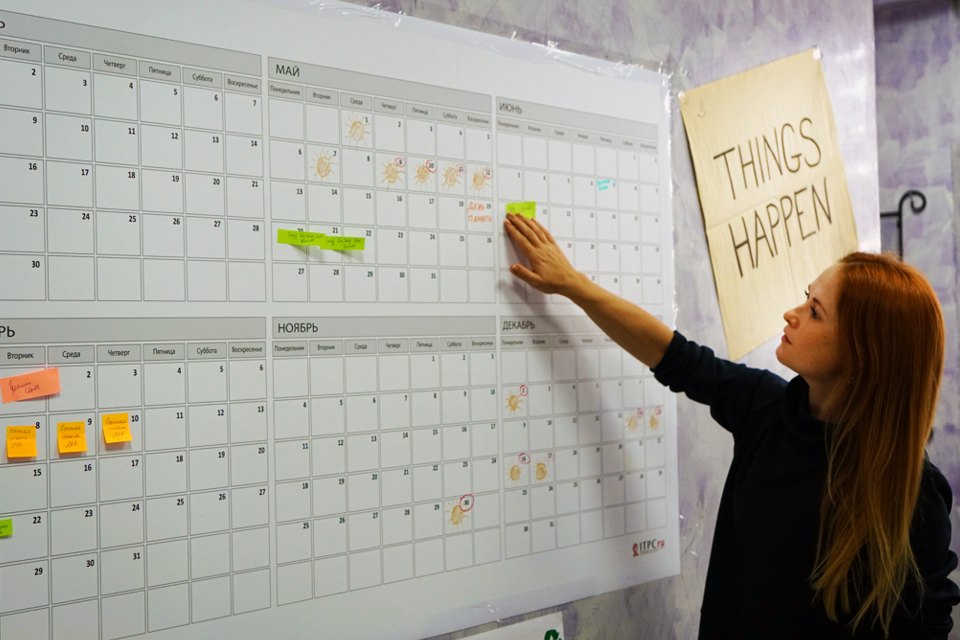

Over the years she has consulted with people in the center as an equal, shared her experiences with therapy and everything one needs to know to give birth to a healthy baby. She gradually began to expand her own knowledge, to learn and read more. Lyubov’s main role now is to analyze, research and gather information.

“I need to know what is going on. You need to examine the documents, you must read a lot, analyze, draft documents, analytical reports, look at the legislation, write reports,” she shares.

Doomed to isolation and death

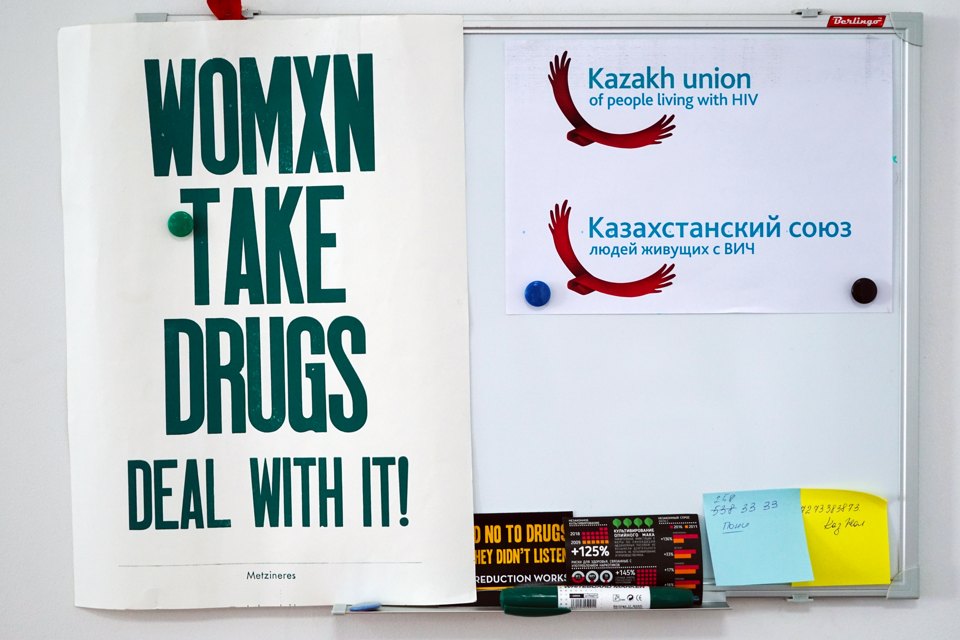

The goal of the human rights organization is to help and support people living with HIV - not an easy task in Kazakhstan.

“I don’t know why, but HIV was dismissed from the national agenda. Maybe there were a lot of reports that everything is already good in this area, they have made progress. But it is not achieved. On the contrary, over the past three years, the death rate from HIV has increased. And when there is treatment, people are dying, this raises questions about the health care system. It means that some mechanisms in the delivery of medical services to the people don’t work," says Lyubov.

Over the past three years, the death rate from HIV has increased. And when there is treatment, people are dying, this raises questions about the health care system.”

Over the past three years, the death rate from HIV has increased. And when there is treatment, people are dying, this raises questions about the health care system.”

— Lyubov Vorontsova.

Diagnostics and drugs are funded by the state, but due to social stereotypes and the stigmatization surrounding HIV, people are unwilling to be treated or tested. Women are persuaded to have abortions or to undergo sterilization. They can lose their jobs.

According to Lyubov, there are many stories that clearly illustrate this situation. She describes one such example. A lone and broke pensioner from Almaty with disabilities spent three days on the streets, being denied rental housing and denied a place at a shelter for older people with disabilities, purely because of his HIV-positive status.

“He was kicked out of the center for the elderly with shouts, complaints, and the verdict ‘you can't live here’. While an Almaty social worker, who was engaged in helping people without a fixed place of residence, was looking for housing for him and negotiated with the city center, this homeless pensioner died - on the street,” Lyubov laments.

When she wrote an extensive post on Facebook, the reaction was swift. The international organization UNAIDS (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS) sent an appeal to the Ministry of Social Protection. Then the Ombudsman joined the call and also wrote a lengthy appeal to the Ministry. In October 2019, at a committee meeting in Geneva, the Kazakh government promised to review the laws regarding people living with HIV.

“At first glance, it looks like a success story. But this is not so. For the sake of change, a man had to die,” Lyubov concludes bitterly.

Fighting criminalization

The Central Asian Association of PLHIV is now addressing the decriminalization of HIV transmission. In Kazakhstan, HIV transmission is a criminal offense that may result in imprisonment. To date, the idea that HIV can be defeated only if everyone is punished still exists as a common mindset.

“Of course, initially, this criminal charge was aimed at stopping the epidemic. But, in practice, it only increases stigma. In a country where there is a criminal prosecution for HIV, society is forming an inappropriate attitude. And people also consider themselves as a criminal element, they have to sign a consent form stating that they are criminally responsible for having this disease,” explains Lyubov.

Remember the power

But suddenly, with sadness and deep faith, Lyubov says: “There is a lot going on in life, and that’s how the world works, to make a woman forget about her strength. This system crushes us with attitudes, beliefs, and the transmission of false values. I would ask women to feel their power because we clearly have one. It is huge. It is healing. It can destroy cities and restore them again. We just need to remember our power.”

I would ask women to feel their power because we clearly have one. It is huge. It is healing.”

Let’s reimagine our world. Equality everywhere. How? Generation Equality has the answers! For the 25th anniversary of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, we asked 25 women to probe still hidden issues and share inspiring ideas on getting transformation going, for good.