Veronica Fonova: Becoming a feminist and leading Kazakhstan’s first feminist rally

Date:

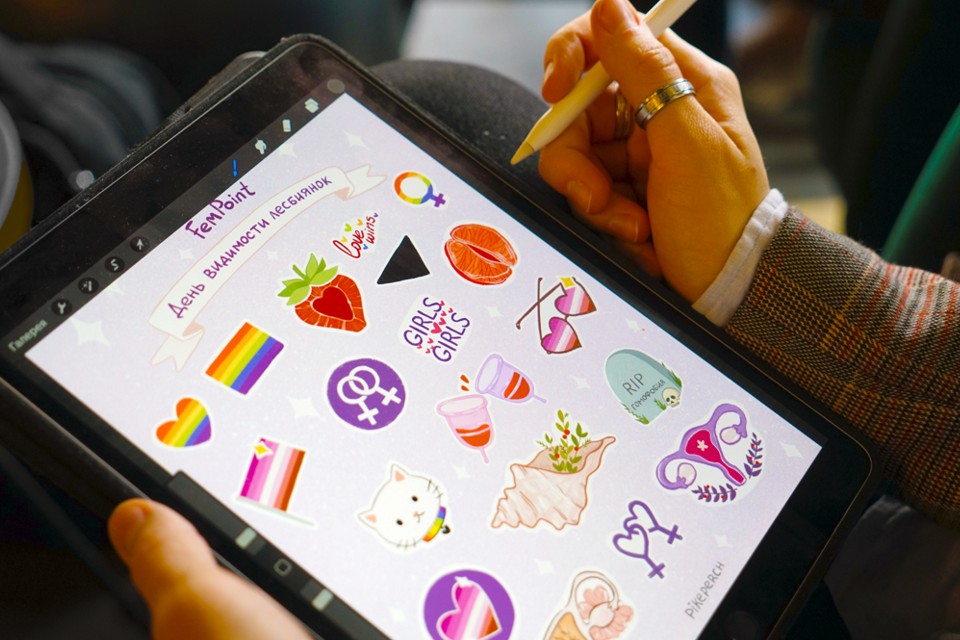

Veronica Fonova, a 27-year-old web designer, became a women’s rights activist after realizing that even in feminist groups the main speakers are still men. She and her friends created the women-only group KazFem, a platform for feminist activism in Kazakhstan. It popularizes feminist ideas and protects women who have experienced discrimination or violence.

“I have put a lot of time and soul into this movement,” Veronica says. “I wanted it to be a safe and comfortable place for women.”

“No one but us can help us,” she declares. “We should take our rights, not ask for them, and be brave and persistent in supporting each other.”

We should take our rights, not ask for them, and be brave and persistent in supporting each other."

We should take our rights, not ask for them, and be brave and persistent in supporting each other."

— Veronica Fonova

A courageous grandmother and a tyrant

Family history triggered Veronica’s activism. She admits that she burns with a sense of injustice and a desire to debunk gender discrimination and inequality.

Born in Almaty, Veronica gratefully recalls her grandmother who was from a small Ukrainian mining town. She fled to Kazakhstan from the tyranny of her husband, when her daughter, Veronica’s mother, was only 8, realizing that they would either be saved or die. When her husband found out about the escape, he searched for her with an ax.

“My grandmother suffered violence for years and could not turn to anyone for protection,” Veronica says. “But she found the courage and strength to escape for the sake of her child, my mother, and lived on.”

The first rally of feminists in Kazakhstan

With KazFem, one of Veronica’s proudest accomplishment has been holding her country’s first feminist rally. In 2017, without prior permission from authorities, women took to the streets with slogans painted on banners, including one that was 6 metres long proclaiming, “Freedom, sisterhood, feminism.”

The event united women from various movements, and was unusual in a country where rallies are generally prohibited. Permission for such an event is required from local authorities, who rarely meet civic activists. This did not deter Veronica. When permission was initially refused for the rally in 2017, she sent 36 applications simultaneously. The authorities finally gave consent and in 2019, KazFem organized Kazakhstan’s first authorized march.

“We were sent to the outskirts of the city. There is one authorized place for rallies and meetings – a small square in a residential area behind the cinema. Nobody walks there,” Veronica says. There was copious criticism from ordinary people and her allies for organizing the march in this authorized but not so visible area. At the same time, she says, “I was rather surprised by the public support. All the friendly media wrote about me.”

At the rally, police detained two non-protesters who had previously threatened the group on the Internet. One was wearing a T-shirt with a “no women” slogan and a crossed-out female character. The police took them away after finding pepper spray in their pockets.

Radical and vulnerable

Activist work defines Veronica’s priorities in life. She is grateful that her employer respects her commitment. But she does not feel safe on the Internet, noting, “When we posted that a march was planned, men wrote comments that they would come and hurt us.”

Authorities, in this case, did not respond. “If the victims of domestic violence are told when you die, then we will come, you have to remain silent about Internet threats,” Veronica says bitterly.

Always dedicated to transforming her concern into activism, she is now working on a website collecting all data on domestic violence cases in Kazakhstan.

“I’m going to analyse the information on several levels, taking into account funding to stop domestic violence, the number of appeals and the number of lines of support, and then compare these figures by region, in line with changes in the legislative framework,” she says.

Gradually, she plans to assess the scale of other troubles: a glass ceiling for women’s salaries, cultural discrimination and infringement of political rights. This, she said, will be a useful base for human rights defenders, journalists and activists.

The most important decision in life

Veronica admits that for most of her life she tried to meet conventional standards, at school, university, home and work. When she allowed herself to begin to speak openly about her sexual orientation, that she loves women, and wants to meet and live with them, everything changed. She does not feel completely safe, however.

“It saddens me very much, it is very difficult psychologically,” Veronica says. “Because I must constantly censor myself, and don’t talk about my partners or love life with other people.”

Veronica encourages women to support each other – and through KazFem has built a critical resource to do so. She points out, “We do not receive funding and never aspired to this, we exist on a voluntary basis. And I believe it makes the movement more honest, flexible and principled.”

She also knows that society has negative notions of women’s groups, assuming that women are always competing with and undercutting each other. But, she stresses, “This is just an instrument of patriarchy, which divides and devalues our struggle.”

“We are different, with different problems, but we are united by the fact that we are women. We will achieve real change if we work together.”

“We are different, but we are united by the fact that we are women. We will achieve real change if we work together.”

Let’s reimagine our world. Equality everywhere. How? Generation Equality has the answers! For the 25th anniversary of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, we asked 25 women to probe still hidden issues and share inspiring ideas on getting transformation going, for good.